Mapping our way to COVID-19 free

What makes the coronavirus so hard to contain since it reached a global pandemic stage is because it is not visible to our naked eye. All we can see is its effect; the symptoms, the spread, and the deaths.

One of the questions that many of us might be pondering ever since our first lockdown is how can we plan and prepare for something that cannot be seen. Well, it turns out there is a way to see coronavirus indirectly, to see its transmitting behaviour, to see how fast it spreads. It is the method used by many data journalists or epidemiologists to collect as much relevant data as possible.

Mapping an invisible killer like the coronavirus is just the same as catching a serial killer. You always need to be ahead of the killer, understanding their behaviour, studying their every move so that you can catch them before they strike again. It also requires both patience and dedication and a robust data collection and reporting system. It is considered both a science and an art form.

The birth of virus mapping has its root in London in the mid-1800s. Back then, people genuinely lived a hard life where medical knowledge and interventions were not as advanced as today’s world. Multiple new diseases were emerging where people had no idea of their whereabouts, let alone how to treat and eradicate them. Many people were contracting and dying from diseases that they had no knowledge of despite the fact that those diseases and viruses are not considered deadly in modern-day terms. One of them is cholera. As a result, people came up with a bunch of weird theories and potential remedies for the disease that lead to inaccurate health advice from wrapping up in hot blankets to taking a teaspoonful of hot water. The advice was not evidence-based and people were generally ill-informed, hence they continued to get sick and die.

The situation took a drastic change when an English physician, John Snow showed up. (By the way, he’s not the Jon Snow from the Game of Thrones). His proposition was simple: tracking every single sick person by talking to them, asking them where they’ve been, what they did, what they touched, and who they came in contact with.

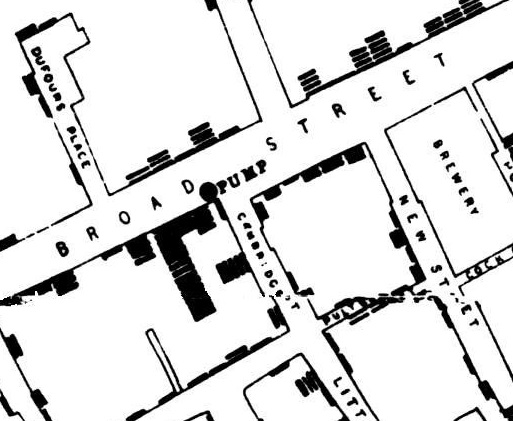

The data he collected all clustered and pointed to a water pump in Broad Street. It turned out that from this data collection exercise, they found out the water supply from the pump was polluted by sewage from a nearby cesspit where a baby’s nappy contaminated with cholera had been dumped. This was a huge revelation because people at the time believed that cholera was transmitted through the air rather than through bodily fluid.

What John produced was not just a simple map of a killer disease, but a detailed statistical analysis. Medicines back then were predicated on each doctor’s knowledge and experience rather than incorporating data science in their daily practice. His work changed the way we practice medicine and also the way we see, visualise and analyse data.

Now fast track to 2020, we are in the midst of a global pandemic. Although, the coronavirus today is very different from the cholera outbreak in the 1850s. (For starters, it is a virus and not a bacteria like cholera). However, what is common between the two is that they both were fast-spreading and infectious. The technique and method required to map coronavirus is virtually the same but on a much greater scale. Rather than trying to map out the virus in a small city, we now need to extend the mapping to countries and even the entire world.

What’s different in today’s world is that people move a lot faster and can travel further compare to back in the 1850s. With that being said, technology these days enables us to track and trace coronavirus in ways we could never imagine and to an extent that can be quite disturbing to comprehend. However, it comes at a cost.

Take South Korea and Singapore for an example. If you were to tested positive for coronavirus, you’ll be interviewed by the police and health officials, and your phone’s GPS signal and credit card transactions will be accessed cross-referenced to retrace your every step. This is to reconstruct a trail of everyone that you have close contact or interaction. Even any objects that you’ve touched will be traced and isolated. Once you are in isolation, all your movements will be monitored and tracked to ensure you do not breach the isolation period. This is the way these countries map out coronavirus to stay ahead of the game. Despite the meticulous, labour, and resource-intensive work involved with this method of mapping, it is possibly the only possible way to truly track the virus and stay ahead of it.

Now a plausible question to ask is why aren’t all countries in the western civilisation utilising this strategy to stamp out the coronavirus? There are several reasons for this. One of the important reasons is that many people in the western world are not comfortable with the idea that their every move is being tracked. We are more sensitive in regards to our privacy being breached compared to some parts of the world. Secondly, this level of tracking requires the government to pour in a large amount of money and funding for it to be possible, and to be frank, many countries do not have the necessary financial resource to do so. Lastly, and is probably the real reason, is that some countries like the United States are simply too late to implement any tracking and mapping of the virus. Many countries did not act or respond quickly enough when there were only a few hundred cases. When it gets over thousands of cases and without a responsive government plan and strategy, it is virtually impossible to map the virus accurately for us to stay ahead of it.

In a way, we all should be extremely grateful for how responsive our government was when handling the pandemic. Obviously, there are things we could have done a lot better but overall, I believe the government has done a tremendous job in preventing NZ from following the footsteps of some other less responsive governments.

Even though we are at alert level 1, there is still a risk of COVID-19 returning to the community. So it is crucial to continue good habits with a face covering, maintaining good hygiene, maintaining social distancing, staying at home if you are sick, and getting a COVID-19 test if you present with COVID-19 symptoms. I also encourage everyone to continue tracking where they’ve been and who they’ve seen to help with the contact tracing app.

It is possible for NZ to continue on level 1 for the long term but it requires all of our input – don’t be complacent!

To a COVID-19 free NZ,